By: Steve Strang

Earlier this year, I came across a number of RFPs proposing a pre-determined set of outcomes that the strategy process should yield. If you build an RFP explaining what your organization needs, why are you hiring outside assistance to restate your needs? Why not just write out the steps it will take to get there?

Defining strategic issues can certainly help focus a strategy formation process, but it’s also a way to foster strategic thinking, to move beyond the notion that nonprofits need “three-year strategic plans” to be effective (the other component that the RFPs all shared).

In today’s fast-changing environment, organizations are forced to make important decisions continually as challenges and opportunities arise. Traditional planning does not easily accommodate for shifts in work plans, resources, or the community. If you are going to take time and resources to jump into a six to eight month planning process, it’s worth investing in an adaptive strategy approach that allows your organization to think and operate strategically, both short and long-term, not just long enough to write the three year plan.

Reasons for Adaptive Strategy in Nonprofits

Imagine you hire a strategy consultant who binds up your three-year plan, that includes more goals, objectives, outcomes, and tactics than you could dream of. It’s 2019, so the plan expires in 2022. Then, the world changes:

- the foundation funding you’ve relied on disappears as the foundation shifts priorities (…or sunsets…or changes leaders).

- a new governor gets elected in your state, creating instability with government funding.

- the market crashes, and the demand for your services increases while revenues decrease.

Of course, this is somewhat of a doomsday scenario, but all of these changes are real, and could happen to nonprofits any day. How can we be so sure about our future needs that we devise a plan to address them for the next three years? We can’t even be sure if it will rain or not tomorrow with absolute certainty, much less answer those thorny questions that challenge our nonprofits.

A More Adaptive Process

Since moving away from the comfort of a three-year plan is the responsible, strategic thing to do, what does it actually look like to implement a more adaptive strategy in nonprofits?

Create Foundational Documents

Using what’s usually considered “formal strategic planning” time (ie: board meetings, staff retreats, senior leadership meetings, etc.), create or revisit your foundational strategy documents. These may include:

- the list of strategic issues your organization needs to address

- intended impact (which compliments a mission statement), or

- impact strategy / theory of change.

These documents serve as long-term beacons for the organization to come back to as needed. In your meetings, worry less about what February 2021’s work plan looks like, and focus on questions like:

- What does success look like?

- If we went away, who would it matter to?

- Is our current operational model working to accomplish our impact?

(Use these big picture questions to ensure that all voices are heard, from the board chair to the receptionist. Each person will provide insights from a different vantage point, and the best ideas don’t always come from the top).

These foundational documents typically total about four pages and serve as the guiding plans the organization lives by. That is, until the metrics selected to monitor progress toward impact indicate that a shift is needed. Just because it’s not a 30-page document in a binder with a set timeline does not mean the process is easier or less important. It’s simply a more adaptive and long-term set of documents. After all, if you can communicate why you exist and how you get there in a few pages, it makes strategy much more accessible, and involving board and staff much easier.

Implement, Monitor, and Revise

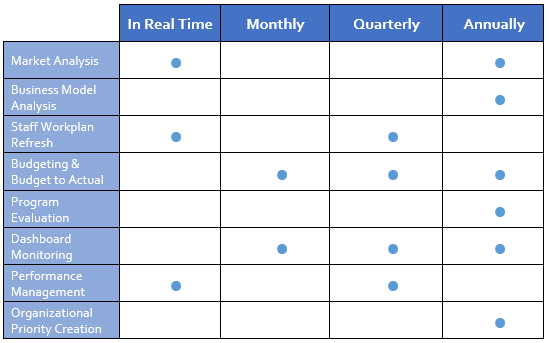

Once you agree on the direction, it’s time to implement, monitor, and revise. Unlike traditional planning, there are not two-and-a-half year gaps in strategic conversations in the adaptive approach. The chart below indicates our recommendation of how frequently your organization could address each of the components listed.

As you learn from implementation and realize an existential shift in impact is needed, you can always go back to your foundational documents and assess (though, done well, those shouldn’t need large changes very frequently).

An important benefit of operating in this manner is that strategy becomes less scary. Instead, strategy brings people in your organization along, promoting shared leadership and building a pipeline of knowledgeable and invested board and staff members.

A Starting Point

Start changing the culture of strategy within your organization using the budgeting process. The budget serves as your hypothesis of how your organization will maximize its impact for the year. Creating a formal learning and review process before (and after) you create your annual budget is a good way to start becoming more adaptive. Instead of just modifying numbers from a previous year, take the results of your budget and program outcomes and evaluate those against your impact and strategies. Are there strengths or areas of concern that you’ve been missing? Do you need to make a small pivot next year based on your learning? There’s no need to shock the system and change everything you do all at once, but starting to break old strategy habits and build new ones can lead to a stronger organization over time.

Interested in the theoretical underpinnings of adaptive strategy in nonprofits? Pull up one or all of these pieces while you’re at the beach this summer: